|

above and below:

Exterior views of St Bertoline

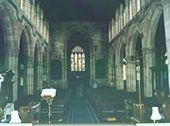

Below:

Interior view of nave looking west

towards the tower arch and base of

the west tower.

|

Cromwellian Britain - Barthomley

Church - Cheshire

The village of Barthomley lies near the south-eastern

boundary of Cheshire, close to the border with Staffordshire. Although

it is less than a mile from junction 16 of the M6 and is bypassed by the

busy A500, it remains a small, peaceful, rural village. Agriculture has

long dominated the life of the village and Barthomley is encircled by

farms which work the now enclosed heath and mossland of the area. The

Wulvarn Brook, running through the settlement, is named in memory of the

last wolf in England, supposedly killed in Barthomley Wood. The village

itself, with its seventeenth century black and white half timbered

cottages as well as more modern houses, clusters around the junction of

two country lanes. At this junction stands The White Lion Inn, dating

from 1614 and formerly the home of the parish clerk. But by far the

largest building in Barthomley, overshadowing and dominating the

village, is St Bertoline’s Church.

The church, with its very rare dedication to an eighth century saint who

performed a miracle here, stands on an ancient barrow mound. There may

well have been a church here in the Saxon period, but the present church

apparently contains nothing older than the late eleventh century. A

Norman doorway, with its distinctively patterned round arch, survives

from the rebuilding of c 1090; now blocked, it is set into the north

wall. Most of the present church dates from the fifteenth and early

sixteenth centuries. Built of local red sandstone, it comprises a heavy

western tower, nave, southern and northern aisles and a chancel. Slight

variations in the design of windows and pier capitals suggest that,

although everything is essentially Perpendicular in style, the church

was not of one build, but was extended and added to over several decades

or generations. St Bertoline’s was restored, sympathetically and without

the drastic alterations to the existing fabric, in the mid nineteenth

century. In the 1920s the chancel and chancel arch were largely rebuilt,

but otherwise the main structure remains in essence as it would have

been in the Tudor and Stuart period, complete with the carved oak

ceiling above the nave. However, with the exception of the carved

Elizabethan altar, most of the fittings – font, pews, pulpit and

coloured glass – are fairly modern.

The church retains several important links with the early and mid

seventeenth century, many of them connected with the Crewes. In the

seventeenth century the parish was dominated by a branch of the powerful

Crewe family, whose seat of Crewe Hall lies less than three miles to the

north-west. Sir Ranulphe Crewe (b 1558), who built the present Hall in

the opening decades of the seventeenth century, was a serjeant-at-law

under James I, served as Speaker of the House of Commons in the brief

parliament of 1614 and was knighted in the same year, and was created

Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench in 1625, just before James I’s

death. However, he was one of a number of senior judges who questioned

the legality of forced loans during the opening year of Charles I’s

reign and was dismissed by the king in November 1626. The aged Crewe

took no active part in the civil war. He died in London in January 1646

but chose to be buried at Barthomley church, in the new chapel which he

had built for his family on the south side of the chancel, abutting the

east end of the south aisle. Although Sir Ranulphe himself has no

visible funereal monument, the Crewe chapel contains mural monuments to

several of his descendents, as well as fine recumbent effigies of

earlier and later figures. At the north end of the north aisle is a

second Crewe enclosure, a late Elizabethan oak screen, carrying carved

inscriptions, which formerly surrounded the family pew. It now encloses

the nineteenth century organ.

Affixed to the wall by the door of the Crewe chapel are four brass

plaques, dating from the seventeenth century and commemorating members

of the Malbon family of Bradley Hall, Haslington; the Hall, which no

longer exists, stood about four miles to the north-west. A stone tablet

now affixed to the south wall of the south aisle records another Malbon,

Thomas, sometime attorney at Chester, who died in 1658. Born in 1578,

Thomas Malbon practised law in both Nantwich and Chester, and rebuilt

Bradley in the opening decades of the seventeenth century. Like Sir

Ranulphe Crewe, he was too old to fight in the civil war, but Malbon

clearly supported the parliamentary cause, playing a minor role in the

wartime administration of the area. In 1651, after the war was over, he

wrote ‘A breefe & true Relacon of all suche passages & things as

happened & weire donne in and aboute Namptwich in the Countie of Chester

& in other plac[es] of the same Countie’. A lively and colourful history

of the civil war 1642-48, focussing on the area around Nantwich, but

encompassing most of Cheshire, Malbon’s account is one of the principal

sources for the history of the civil war in Cheshire. It was almost

immediately paraphrased and plagiarised by Edward Burghall, vicar of

Acton in the 1650s, who cobbled together his own manuscript account of

the war in Cheshire, ‘Providence Improved’. In 1889, both accounts were

edited by James Hall and published by the Lancashire and Cheshire Record

Society.

We know a little about Barthomley’s incumbents at this time. For part of

the war years, the living was held by George Mainwaring, member of

another old Cheshire family with tentacles in many parts of the county;

the Crewes had married into a branch of this family in the sixteenth

century. From 1649 until 1684 the incumbent was Zachary Cawdrey. In

1647, while a fellow of St John’s College, Oxford, he had been in

trouble with parliament for ‘using the Prayerbook against Protestant

orders and praying to the King’. But Cawdrey retained the parish

throughout the 1650s and the Restoration period. A silver chalice and

paten which he gave to the church are still in use. The author of a

number of minor religious works published during the 1670s and early

1680s, Cawdrey died in 1684. A brass plaque, now affixed to south

chancel wall, records not only his own death but also that of his wife,

three years earlier.

Barthomley church has a much stronger and darker claim to fame and has

an infamous niche in the history of the civil war, for it was here that

one of the most notorious massacres of the war took place. The basic

facts are clear enough. Bolstered by newly arrived reinforcements from

Ireland, in the closing days of 1643 the Chester royalists sent out

parties to harry the parliamentarians, who controlled much of the

county. On 23 December royalist troops entered Barthomley. Malbon gives

a graphic account of what followed:

‘The Kinges p[ar]tie comynge to Barthomley Churche, did sett upon the

same; wherein about xxtie Neighbours where gonne for theire saufegarde.

But maior Connaught, maior to Colonell Sneyde,...w[i]th his forces by

wyelcome entred the Churche. The people w[i]thin gatt up into the

Steeple; But the Enymy burnynge formes, pewes, Rushes & the lyke, did

smother theim in the Steeple that they weire Enforced to call for

quarter, & yelde theim selves; w[hi]ch was graunted them by the said

Connaught; But when hee had theim in his power, hee caused theim all to

be stripped starke Naked; And moste barbarouslie & contr[ar]y to the

Lawes of Armes, murthered, stabbed and cutt the Throates of xii of theim;...&

wounded all the reste, leavinge many of theim for Dead. And on Christmas

daye, and Ste Stevens Daye, the[y] Contynued plu[n]dringe & destroyinge

all Barthomley, Crewe, Haslington, & the places adiacent...’

Of the twenty ‘neighbours’ who had been smoked out of the steeple,

twelve (all males, named in Malbon’s account) were killed on the spot

and many of the remaining eight badly wounded. They seem to have been

cut down at the base of the tower, and thus within the church itself. By

26 December Lord Byron, royalist commander in Chester, was crowing to

the Marquis of Newcastle:

‘the Rebels had possessed themselves of a Church at Bartumley, but wee

presently beat them forth of it, and put them all to the sword; which I

finde to be the best way to proceed with these kind of people, for mercy

to them is cruelty.’

Malbon’s account, largely followed by Burghall, portrays the event as a

completely unprovoked and unlawful attack upon villagers who had

surrendered at Connaught’s promise of quarter. Other accounts, however,

suggest that the sequence of events may have been rather different. In a

letter of 9 January, John Byron claimed that the royalists had initially

issued a summons to the men inside the church but that it had been

refused. Only then did the royalists attack and capture the church,

possibly having to fight their way in. Although in the civil war quarter

was usually then given at that point, there was no legal obligation to

spare defenders who had spurned a formal summons and had pushed the

issue to violence and bloodshed. Although very unusual, the capture of

Barthomley church was not the only occasion during the civil wars when,

in such circumstances, the attacking force proceeded to put the

defending force to the sword. Some historians have suggested an

alternative sequence of events to explain the bloodletting – that having

initially agreed to surrender on offer of quarter, one of the villagers

wounded or killed a royalist soldier, thus negating the agreement and

provoking what followed.

Whatever the exact sequence of events at Barthomley church on 23

December 1643, the killings became notorious. Eleven years later, at the

Chester assizes of October 1654, vengeance was exacted. John Connaught,

formerly a royalist major, was tried for his life. Although he was

charged with murdering ‘several persons’ in the church, the trial

focussed on the death of just one of them, John Fowler. The jury heard

that Connaught, with a battleaxe (valued at 6d) in his right hand, had

caught hold of Fowler and struck him on the left side of his head,

inflicting a wound which, though only one inch long and one inch deep,

was instantly fatal. The jurors found the case proved, Connaught offered

nothing in mitigation and John Bradshaw, who five years before had

presided over the king’s trial, passed sentence of death. Connaught was

hanged at Boughton, on the outskirts of Chester, on the aftemoon of

Tuesday 17 October 1654. According to the diarist, Henry Newcome, he

went to the scaffold protesting his innocence:

‘The matters he died for were clearly proved, and yet he seemed to take

a great glory in his innocency, and would freely tell of his other sins,

as gaming, drinking, nay

conjuring, which were some of them not known, and yet would stand in the

denial of a thing that was proved.’

It is now hard to believe that this attractive church in its quiet rural

setting once witnessed such horrors as those of Christmas-time 1643. St

Bertoline’s is still in regular use for services. It is in good

condition and is well kept. It stands amidst an equally interesting

churchyard, and an unusual number of well preserved early eighteenth

century gravestones – a handful date from the latter half of the

seventeenth century – are now laid to form a path around the outside

walls of the church. St Bertoline’s itself is generally unlocked and

open to visitors during the day. Sadly, because of the threat of

vandalism, the Crewe chapel is normally locked, though a notice directs

visitors to the adjoining modern rectory, where the key may be sought.

By Dr Peter Gaunt.

|