|

Exterior view of St Pancras, with its soaring

granite tower

Interior view of the nave,

looking East

The inscrbed tablet to Mary,

wife of John Elford,

who died in February 1643

The tombstone of Roger Hill,

who died 21 October 1638,

and his wife Ann, who died

ten years later.

|

Cromwellian Britain

- Widecombe-in-the-Moor, Devon

Dartmoor, like most of the upland reaches of Britain,

was not actively fought over during the civil war. A high moor, thinly

populated, with no significant urban centres and, despite its mineral

deposits, in the seventeenth century not particularly affluent, it

possessed neither the resources nor the easy lines of communication to

make it attractive to rival armies. Devon as a whole was hotly contested

and changed hands twice. Initially held for parliament, it fell to the

king in 1643 and remained in royalist hands until 1645-6, when it was

recaptured by Fairfax, Cromwell and the New Model Army. There was

significant action along the roads and in and around the townships which

fringed the moor. In the opening months of the war, the two sides

clashed around Dunsford and, in February 1643, at Chagford, resulting in

a street fight in which the royalist poet Sidney Godolphin was badly

wounded and reputedly bled to death in the porch of the Three Crowns; in

April 1643 local parliamentarians ambushed a party of Cornish royalists

on Sourton Down and a running fight developed; and in January 1646, as

part of the parliamentary reconquest of the county, Cromwell himself

attacked and scattered royalists camped outside Bovey Tracey.

Although the heartlands of Dartmoor largely escaped direct fighting,

they certainly contributed men who fought and in many cases were killed

elsewhere. Mark Stoyle has recently portrayed early Stuart Dartmoor,

along with much of mid Devon, as a somewhat isolated region of the

county, far removed from the new ideas and new influences found in the

ports and the main urban centres. There was a relatively static

population – Stoyle found that of the 107 family names recorded in the

moorland parish of Widecombe between 1600 and 1634, 51% were still there

in the period 1700-34, a much higher figure than found in other parts of

Devon and elsewhere in England – which was conservative in religion,

resisting reformist ideas, and which retained the old customs of church

ales and popular festivals. In the light of this it is not surprising to

discover that this was an area of popular royalism, in clear contrast to

the north, south and parts of the east of the county, which showed

evidence of popular parliamentarianism. Records of those killed and

maimed in the king's service suggest that many of the parishes of mid

Devon in general and Dartmoor in particular contributed a much higher

proportion of adult males to the royalist armies than parishes elsewhere

in the county.[1] Although the heartlands of Dartmoor largely escaped direct fighting,

they certainly contributed men who fought and in many cases were killed

elsewhere. Mark Stoyle has recently portrayed early Stuart Dartmoor,

along with much of mid Devon, as a somewhat isolated region of the

county, far removed from the new ideas and new influences found in the

ports and the main urban centres. There was a relatively static

population – Stoyle found that of the 107 family names recorded in the

moorland parish of Widecombe between 1600 and 1634, 51% were still there

in the period 1700-34, a much higher figure than found in other parts of

Devon and elsewhere in England – which was conservative in religion,

resisting reformist ideas, and which retained the old customs of church

ales and popular festivals. In the light of this it is not surprising to

discover that this was an area of popular royalism, in clear contrast to

the north, south and parts of the east of the county, which showed

evidence of popular parliamentarianism. Records of those killed and

maimed in the king's service suggest that many of the parishes of mid

Devon in general and Dartmoor in particular contributed a much higher

proportion of adult males to the royalist armies than parishes elsewhere

in the county.[1]

Widecombe-in-the-Moor was and is a large parish in the eastern half of

Dartmoor. Although the village itself lies in a slight valley, the land

rises steeply above the settlement, and in the seventeenth century, as

now, it was an area of scattered farms, with rough grazing for sheep and

cattle, and tiny hamlets. At the time of the civil war the adult male

population of the entire parish probably totalled less than 150.

Nevertheless, there is evidence of some wealth in the area, most obvious

in the surprisingly large and elegant parish church of St Pancras with

its soaring, late medieval tower, probably built out of the profits of

medieval tin-working in the locality. Now rather too popular for its own

good during the summer months, Widecombe has become well known for its

fair and associated song, and for the large numbers of tourists and

coaches which converge upon it. But at heart, and particularly out of

season, it remains a very attractive village, especially the small

square on rising ground, framed by the church and churchyard, the Glebe

House of 1527 and the Old Church House, dating from the sixteenth or

early seventeenth century, which has served at different times as

alehouse, poorhouse, schoolhouse and almshouses.

Although there is no record of fighting here during the civil war,

Widecombe acquired considerable fame or notoriety in the mid seventeenth

century because of the terrible storm which hit the village in autumn

1638. News of the events quickly spread through England and within a

week or so of the storm, a pamphlet describing ‘those most strange and

lamentable accidents’ was published in London. It quickly sold out and a

second, larger account was produced.[2] Together, they provide a graphic

and at times gory description of the events which occurred in Widecombe

on Sunday 21 October 1638, during divine service, as allegedly recounted

by eye-witnesses who had ‘now come to London’. The authors justified the

pamphlets by pointing to the lessons which all might learn from God’s

dramatic intervention in the world:

‘GODS visible judgements, and terrible remonstances...comming unto our

knowledge, should be our observation and admonition, that thereby the

inhabitants of the earth may learn Righteousnesse, for to let them pass

by us...unobserved, argues too much regardlessnesse of GOD in the way of

his Judgements...But to heare and feare and to doe wickedly no more, to

search our hearts and amend our waies is the best use that can bee made

of any of GODS remarkable terrors manifested among us. When GOD is angry

with us, it ought to be our wisdome to meete him, and make peace with

him...Except wee repent, wee shall likewise perish...Therefore this

should awe and humble our hearts before the LORD, rising up into more

perfection in godlinesse, doing unto our GOD, more and better service

then ever hitherto wee have done, reverencing and sanctifying his

dreadfull Name in our hearts, especially when his Judgements breake in

upon men, even in his owne house, mingling their bloud with their

sacrifices, and in that most terrible manner smiting, and wounding, and

killing, as in this ensuing Relation may appeare...The Lord teach thee

to profit thereby, that it may bee as a Sermon to thee from Heaven by

the Lord himselfe.’

The two accounts which followed described how the sky darkened strangely

during the Sunday service, so that the congregation could not read their

books and could barely see one another, closely followed by ‘a mighty

thundering’ and ‘terrible strange lightening’. The lightening struck the

church tower, badly damaging it and causing one of the corner pinnacles

to collapse through the roof of the nave. Either that bolt or a second

strike entered the nave itself in the form of ball lightening, and some

of the congregation recalled seeing ‘a great fiery ball come in at the

window and passe through the Church’, accompanied by fire, smoke and a

strong smell of brimstone. Most of the congregation threw themselves to

the floor amidst great cries ‘of burning and scalding’. The minister,

George Lyde, was in the pulpit when the lightening struck, but even

though it passed close by, leaving one of the faces of the pulpit ‘black

and moist as if it had beene newly wiped with Inke’, he was unhurt.

However, ‘the lightening seized upon his poor Wife, fired her ruffe and

linnen next to her body, and her cloathes, to the burning of many parts

of her body in a very pitifull manner’. A friend sitting next to her was

also ‘much scalded’ and another unnamed woman ran out of the church with

her clothes on fire and was left not only ‘strangely burnt and scorched,

but had her flesh torne about her back almost to the very bones’. Two

male members of the congregation were killed, Roger Hill and Robert

Meade, warrener to Sir Richard Reynell, both apparently by being thrown

back so violently by the lightening that their heads were smashed

against the church wall. The accounts describe in detail how the

unfortunate warrener has his skull smashed open so that his brains were

thrown out and a bloody indentation made in the wall. Many others were

injured, some of whom subsequently died: a woman who ‘had her flesh so

torne and her body so grievously burnt’ died the following night and a

man sitting close to the warrener was burnt all over and lingered ‘in

great misery’ about a week. On the other hand, there were remarkable

escapes, of people whose hats or clothes were burnt off but their bodies

left untouched, of small children forgotten and abandoned in the ensuing

chaos who wandered out of the ruins unharmed some hours later: ‘but it

pleased GOD yet in the midst of judgement to remember mercy, sparing

some and not destroying all’.

The church itself was badly damaged by the lightening. The ball

lightening within the body of the church burnt or overturned pews,

scorched the stonework and caused one of the main beams to collapse,

though it fell harmlessly to the floor between the minister and the

clerk. The tower was also badly damaged and its partial collapse in turn

damaged the roof of the nave. The following day two volunteers ventured

up the wrecked tower, despite the ‘loathsome smell beyond expression, as

it were of Brimstone pitch and sulphur’, to inspect the damage. One

turned back in fear and the other was violently sick that night. On the

Monday, too, the minister conducted a joint service for the first two

victims, Hill and Meade, who were buried side by side at the east end of

the nave; when Lyde threw some earth onto the coffins, the sudden noise

caused those attending the funeral to ‘runne out of the Church, tumbling

over one another supposing that the Church was falling on their heads’.

The lightening strike at Widecombe church was referred to nearly twenty

years later, in a pamphlet addressed to the Protector and the second

Protectorate Parliament, attacking ‘the Idolatrous High-places which are

still kept up, under pretence of usefulness and convenience of Worship’.

The pamphlet, which George Thomason dated 10 December 1656,[3] comprises

an outspoken attack upon church towers and steeples and the bells housed

within them, as ‘useless...unprofitable...idolatrous’, ‘to be utterly

destroyed’. ‘Are they [steeples] not the Pope’s pillars? for they were

erected by the Catholic Papists, in honour of their Popish gods...Down

with them and their Babylonish Bells, to the very ground, and let not a

stone of them remain upon another’. The anonymous author, possibly

Samuel Chidley, notes with approval that the year before God had caused

a thunderbolt to strike ‘Sin Botolphs Steeple at Boston’. Although the

events at Widecombe are not discussed in the main text, the pamphlet

opens with a verse –

‘Protectors, Parliaments, and all, see, hear,

And quake for fear: O do not jeer, nor swear

‘Gainst God, who roars from Sion on your sin,

‘Gainst such High-places which you worship in.

J[ehov]ah with his burning blasts of lightening quells

The Peoples Idols-Temples-Steeples-Bells’

– below which is reproduced a crude engraving of the lightening strike

on Widecombe church on 21 October 1638, with the note ‘A most prodigious

& fearefull storme of winds lightening & thunder, mightily defacing

Withcomb-church in Devon, burneing and slayeing diverse men and women

all this in service-time’. The engraving shows one bolt hitting the

church tower, causing a pinnacle to collapse, and another fiery ball

heading for the nave. The near wall of the nave has been removed so that

the illustrator can depict the chaos inside. There is fire and smoke in

the nave, members of the congregation are in disorder, a male figure

lies face down in the foreground and part of a pillar or beam is falling

close to the pulpit, in which the mmister stands.

Widecombe church, which is generally unlocked and open to visitors,

contains several echoes of the great storm. The village schoolmaster at

the time, Richard Hill, wrote a long poem about the storm, which was

painted on boards in the church. The present set of boards, now hanging

in the base of the tower, are replacements made in the 1780s. At the

east end of the nave, close to the chancel, can be seen the gravestone

of one of the victims, which bears a still legible Latin inscription

showing that it is the resting place of Roger Hill, gentleman, who died

on 21 October 1638, and of his widow Anne, who died ten years later. A

similar gravestone next to it, without an inscription, probably marks

the burial place of Robert Meade, the warrener. Two other features of

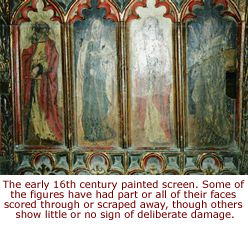

the splendid, principally Perpendicular church should be noted. Although

the upper part of the wooden screen and its rood loft have long gone,

the lower part, probably of the early sixteenth century, survives,

complete with paintings of various saints and martyrs. Several have had

their faces scored through or scraped away. Although such defacement is

invariably ascribed to civil war iconoclasm, there is here, as in so

many churches, no evidence to link it to the mid seventeenth century.

The iconoclasm of the opening stages of the sixteenth century English

Reformation, or post-early modern vandalism, might just as easily be to

blame. And on the north wall of the nave is an inscribed tablet to Mary,

third wife of John Elford of Sheepstor. Married in February 1641/2, she

died in February 1642/3, shortly after the birth of her twin daughters,

and was buried here. The elaborate tablet, erected in 1650, commemorates

her in verse. The inscription notes that her name, Mary Elford, is an

anagram of ‘Fear My Lord’, and includes within it various characters

which, read as Roman numerals, give her age at death (25) and the year

of her death and burial (1642 old style).

Notes.

-

Mark Stoyle, Loyalty and Locality. Popular Allegiance in

Devon during the English Civil War (Exeter, 1994).

-

A True Relation of those most strange and lamentable

Accidents, happening in the Parish Church of Wydecombe in Devonshire and

A Second and Most Exact Relation of those Sad and Lamentable Accidents

which happened in and about the Parish Church of Wydecombe neere the

Dartmoores. Both have been reprinted with a brief introduction and notes

by M Brown, The Great Storm at Widecombe, 21 October 1638 (Plymouth,

1996).

-

British Library, Thomason Tract, E 896 (9). The British

Library catalogue lists the pamphlet as a work of Chidley.

By Dr Peter Gaunt

|